When you’re trying to get a new concept or campaign off the ground, there’s nothing worse than the person who sits back pricking holes in your ideas while you’re trying to float them.

There is a way to use that Negative Nellie or Nigel for the good of the company – put them on the Red Team!

The concept of Red Team/Blue Team has been used in military strategizing for a long time and, like so many warlike terms, has also been incorporated into cybersecurity practice. Don’t be put off by this, it also has enormous potential to improve marketing campaigns.

Red Team/Blue Team is a strategy where one group – typically an external “Red” team, attempts to find weaknesses in the internal “Blue” team’s activities.

In a military setting, the term Red Team is traditionally a highly skilled and organised group acting as a fictitious enemy to test the “regular” squads’ (the Blue Team’s) force-readiness with sudden, realistic assaults.

Red Teams have also been used to test the physical security of sensitive sites like nuclear facilities and government offices.

In the cybersecurity field the Red Team’s hostile activities take the form of sophisticated penetration tests, providing a reliable assessment of an organisation’s defensive capabilities and its safety status.

So how does a bunch of creative marketers benefit from a strategy that often involves brute force (in both the military and cybersecurity meanings of the word)?

Firstly, we have to make sure that this strategy isn’t just seen as a battle between two opponents, with one winner and one loser. Both teams need to recognise they are working for a common purpose, such as a calamity-proof campaign, and agree to share their findings in a constructive way.

Secondly, we must recognise that sometimes we are too familiar with our creations. We spend a lot of time working on these projects, we create innovative ideas and we are often passionate about them – and these are good things – but this can mean we are blind to potential problems. Our customers are going to be coming to the product, or campaign, or event, without that level of intimacy, so while the jump from climate change to travel insurance is an obvious step in our minds, for outsiders it may require the crossing of a bridge too far.

Your Blue Team could be made up of your marketing or communications people who are working on the particular project. This might be a marketing plan for a new product, a media campaign or an event plan. The Blue Team will have included the usual SWOTs and well-thought out SMART objectives. You think you’re set to go.

Then, you pitch it to the Red Team. A bunch of nit-pickers who aren’t blinded by the brilliance of your baby. In fact, up until now they’ve known next to nothing about it at all.

And that’s when the “what-ifs?” and “but whys?” start. It’s a bit hard to swallow, but healthy – like bran for breakfast.

The Red Team should comprise some marketing or communications people who aren’t working on your particular project who will pick up any marcomms or PR pitfalls in the plan. It should also include a couple of colleagues with completely different roles, for example Bill from accounting, whose child has a peanut allergy, or Eva from legal, who not only sees a lawsuit in every creative move, but also is bilingual and points out the sizable audience you are about to alienate with the name for your new product.

For example, if Honda had a Scandinavian speaker on their creative team, they probably wouldn’t have called their cute little car the Fitta, which is Norwegian slang for female genitals. Lacking a Red Team, red-faced Honda folk had to change the car’s name post-launch to Honda Jazz.

Car makers seem especially prone to this kind of pitfall, so we’ve had the Mitsubishi Pajero (Spanish for masturbator); the Chevy Nova (“no va” in Spanish means “not going”); and the Renault Wind, which is relatively harmless, apart from the various puns about people passing a little Wind on the highway.

Another example where a Red Team inspection (or “interference” as creatives prefer to call it) would have helped was last year’s unfortunate UK online soccer ticket competition run by Pepsico for its Walkers Crisps brand.

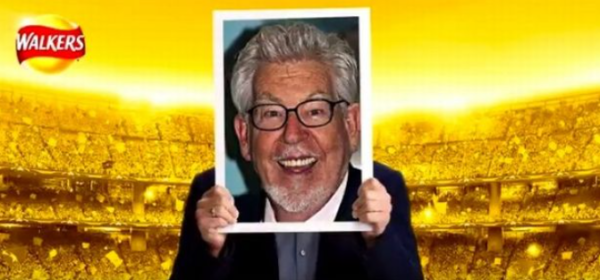

The competition, which offered Champion’s League tickets, invited people to tweet selfies that would be featured alongside former champion Gary Lineker in an automated video. The trouble started when people realised that the video generator wasn’t being monitored by a real person and would accept any photo that was recognised as a human face. Soon enough pranksters started tweeting photos of various despots, serial killers and sex offenders, including our own Rolf Harris.

Poor Gary Lineker appeared to hold up a poster of each criminal in front of his head, then point out their “face” in the crowd doing a Mexican Wave with other fans, as he wished them luck in bagging a prize.

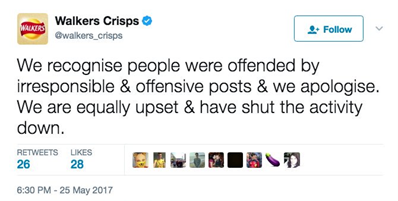

The stuff-up went viral, of course, and Walkers quickly shut down the competition, apologising with a single tweet. Given that the problem arose from the bad behaviour of the public rather than the company, there wasn’t a lot of outrage at the content itself. The Twitterverse did, however, react with sheer disbelief that the campaign creators failed to see such an obvious flaw in their idea.

If the Walker Blue creatives had tested this idea with a Red Team, they may have prevented this situation. Time and resources are always short, but next time your team is about to implement a brilliant creative idea, don’t be afraid to let a Red Team of unbiased outsiders to put it to the test – and be genuinely open to having your ideas challenged.

Why your social media strategy should be thought of as an insurance policy

Social media gets a lot of flak because of the undesirable social effects its use triggers in the personal sphere. In the public sphere, however, it can be a valuable tool for crisis communication. Of course it can also create a crisis, but more of that later.

The immediacy and ubiquity of social media means it can often reach audiences more quickly, and more effectively, than traditional media during a crisis.

A classic example, which has become a template for social media crisis comms, was Dutch airline KLM’s 2010 response to the impact of the Icelandic volcanic ash cloud which threw air travel into chaos.

With flights cancelled and an unpredictable time frame for resolution, KLM was inundated with an unmanageable number of telephone and face-to-face queries.

Like many other organisations at the time, KLM’s social media team and crisis strategy was limited, but the airline staff quickly realised its Twitter and Facebook channels would be the best way to ease the logjam of customer enquiries.

Demonstrating great agility, KLM deployed as many resources into social media as possible, seconding volunteers and staff from various other departments to respond online to stranded passengers.

They apologised for the chaos and invited customers to send a request on Twitter, promising to follow up via DM.

Key to the success of this strategy of course was that they not only apologised and offered a simple alternative, but they delivered on their promise.

Since then KLM has continued to develop its reputation for smart social strategy, although not without hiccups. Within minutes of the Netherlands’ 2-1 victory over Mexico in the 2014 World Cup, KLM’s Twitter feed ran a photo of an airport departures sign under the heading “Adios Amigos!”. Next to the word “Departures” was the image of a man with a moustache wearing a sombrero.

The post immediately went viral, with A-list Mexican actor Gael Garcia Bernal angrily telling his 2 million-plus followers that he’ll never fly with the carrier again. Amid the widespread protest online, the post was pulled a half-hour later without an explanation.

In contrast to KLM’s style, British Airways last year incurred the wrath of travellers when an IT issue grounded its flights, stranding people at Heathrow. It issued one short apology tweet, offering no alternatives for staff, and after several days of Twitter silence responded to passengers’ furious tweets with comments like “hope you’ve now found your luggage” or “trust you made it to your sister’s wedding”, which just infuriated people even more.

The Roseanne Barr social media incident in May this year illustrated some smart use of Twitter. Not by Barr, the less said about that the better, but by Sanofi, the pharma company behind the Ambien sleeping pill. When Barr blamed her poor judgement on her use of Ambien, Sanofi quickly responded with this tweet:

With a single tweet, Sanofi managed to distance itself from the scandal, present itself positively as made up of real people not just a faceless big pharma and reach more than 12 times the audience it can usually access. By grabbing the social media narrative, Sanofi turned a threat into an opportunity. There was still a bit of #bashtagging from people unhappy with Ambien use, but overall it was a huge win.

Of course it is easier to successfully mitigate a crisis if it is not of your own making, and sometimes you can count on the community to help out. Grassroots social media campaigns during the recent Australian strawberry-tampering incidents demonstrated the power of the people.

The crisis arose when a 21-year-old man in Queensland swallowed a portion of a needle after biting into a strawberry and was reportedly hospitalised for abdominal pain. Since then, needles have been discovered in fruits in all six Australian states, according to police, with more than 100 reports in total.

In response, strawberry producers had to dump their products, major grocery chains like Coles and Aldi pulled them from shelves, and Woolworths stopped selling sewing needles at its stores.

The strawberry industry was reeling, with thousands of workers affected. Product tampering is not uncommon, and there is always significant debate about the value of widely publicising such activities (beyond the duty to protect consumers) because media coverage is said to provide offenders with a thrill and trigger copycat incidents.

Initially, Woolworths was criticised for its tardiness in alerting the public and their pedestrian legal response in withdrawing the product from sale. Although some brands were not available, Woolworths said it had continued to stock unaffected brands throughout the crisis and had run promotional in-store campaigns to reassure customers.

Initially, Woolworths was criticised for its tardiness in alerting the public and their pedestrian legal response in withdrawing the product from sale. Although some brands were not available, Woolworths said it had continued to stock unaffected brands throughout the crisis and had run promotional in-store campaigns to reassure customers.

Others were more creative and the #SmashAStrawb viral grassroots social media campaign urged people to get behind the embattled strawberry growers.

Savvy politicians jumped on board, eating strawberries at media opportunities and sharing recipes on social. A bipartisan “Cut ‘em up. Don’t cut ‘em out” campaign featured on Twitter and Facebook Social media was used to encourage people to buy direct from the growers and hordes of people flocked to strawberry farms to either buy at the gate or pick their own.

While the long-term damage of the tampering remains to be seen, the timely and effective mobilisation of consumers via social media was an encouraging response to the crisis.

Crises occur for a variety of reasons, controllable and uncontrollable, and can spiral out of control incredibly quickly. We all know we should have a crisis management plan, and that it must include a crisis communications plan, including guidelines on how to respond both publicly and internally, but we often fail to do so.

To misquote Benjamin Franklin: “by failing to plan, you are planning to fail”. So, what’s needed for a successful social media crisis communications plan?

- Play the long game and invest in social media now, not when the crisis hits. Effective social media crisis management is not just about how to respond in the short-term, but finding ways to recover reputation after the incident has subsided.

- Invest in social. Creating quality content is like saving for a rainy day. If you build your Search Engine Optimisation (SEO) you will have a buffer against unexpected withdrawals in your social-licence-to-operate account. SEO leaves a permanent record of your crisis and you need to make sure you consistently produce and disseminate quality content to outrank and outflank any negative coverage of the crisis. Search engines rate content by a range of indicators including popularity, use of organic links, accessibility and the credibility of your URL.

- Establish guidelines for handling social media comms, including approval processes, during a crisis and practise switching from day-to-day into crisis mode, when volumes of incoming material and media interest will be much greater. This should include preparing holding statements, keeping up-to-date lists of staff and volunteers who can be called on, and making sure that everyone has the training they need to jump straight onboard.

- Be mindful of the public record. Respond to threats, claims and questions publicly whenever possible. You need to have your side of the story out there.

- Be timely. Track your social media and get your message out early and keep communicating frequently. Don’t wait to see if traditional media picks it up. By then, you’ve lost control of the narrative.

Managing a successful social media strategy can be time-consuming, however Pesel & Carr can help you formulate and implement an appropriate plan so you won’t be caught on the back foot.

final word from our culture manager

I was smelling the flowers in the local park the other day – well, I was really reading the canine news, finding out who’d been where etc, but I think Barbara likes the idea of me being a flower aficionado – and I noticed a young Lab called Marcy getting very worked up trying to figure out what her human wanted. The human was on his phone, trying to stop his coffee from spilling while he ordered Marcy to sit and stay, but Marcy was bouncing around the place, barking and getting progressively more anxious as it became obvious her human wasn’t happy with her.

“Sit, no sit down, no! Sit! Yes! Stay, no! Marcy, wait! Shut up! Sit! Marcy, go back! Look at me, Marcy, Marcy! Here! Heel!” he shouted.

Marcy was not only upset that she was stuffing her tasks up, but she couldn’t keep her eyes off a mini-human who was running around in circles nearby making a high-pitched squealing sound, a bit like a cat you’ve just caught. If I wasn’t so well-educated, I probably would’ve dashed straight over for a squiz myself.

Anxiety in dogs isn’t that unusual. We’re a sensitive lot, desperate to please our humans and often finding ourselves unable to relax and get the commands right. I’ve noticed similar behaviour in humans who spend their days in corporate kennels. They want to do well in the kennel, but when they have information overload, or don’t get clear instructions because no one has time to explain things to them, or are expected to perform business tricks without the resources they need, they get really anxious too. They often don’t call it that, though, they prefer to call it “stress” because it sounds like the sort of thing you get from being really busy or indispensable, whereas “anxiety” is associated with weakness.

I watch them go past our corporate kennel window. They scurry along, earplugs cutting them off from the natural world, wolfing down a sandwich, checking the shopping list in their hand, wondering if there’s really time to do the grocery shopping at lunchtime and trying to figure out how they’ll get that acquittal report done before COB.

Apart from unclear instructions and unrealistic expectations, multi-tasking is also a significant cause of anxiety because it contributes to sensory overload.

Humans talk a lot about mindfulness, but almost everything they do seems to prevent them from actually being in the moment – that feeling of just lying on the feet of your loved one, enjoying the smell of them and thinking about … nothing.

That’d probably do Marcy good too – just being the centre of her human’s attention, with no phone, no mini-humans in tow, no coffee. After all no one likes being peripheral.

She can’t multi-task either. Not yet, she’s only a pup. If she does “sit”, she needs praise and only when she’s really confident about that can she cope with “stay”. And her human needs to make up his mind – is she going to “stay” or “wait”? If she’s going to learn “down”, he shouldn’t say “sit down”. He also needs to decide if he leads with his left or right foot. If he’s consistent, she’ll learn that left foot means heel, and right foot means stay. Consistency doesn’t seem to come easily to a lot of humans.

If Marcy’s getting bombarded with too many, ambiguous instructions she’ll just make even more mistakes and get really anxious. So whether you’re with your loved one in the park, or colleagues in the corporate kennel, give clear instructions; have patience; keep it simple; and be consistent.

Woof!

Louis